Authors: Mehrzad Boroujerdi and Kourosh Rahimkhani

New York: Syracuse University Press, May 15, 2018. Read more

News

Einsicht (Insight and Understanding)

Edited by Boris von Brauchitsch and Saeid Edalatnejad

Heidelberg: KEHRER Verlag, 2017 Read more

Sociology of Shi’ite Islam

Saïd Amir Arjomand

The Sociology of Shi’ite Islam is the collection of scholarly articles by a historical sociologist applying a Weberian sociological framework for the historical analysis of Twelver Shi‘i Islam. This book encompasses the comprehensive socio-historical analysis of Twelver Shi‘i Islam from its sectarian formation in the eighth century to its establishment as the national religion of the Safavid Empire in the sixteenth century and down to the Islamic revolution and the formation of a Shi‘i theocratic state in Iran in the late twentieth century.

This book is comprised of nineteen essays grouped into four parts. The first part addresses the historical formation of Shi‘ite Islam from the eighth to thirteenth centuries CE. Author Saïd Arjomand builds his sociological framework upon some Weberian ideas—especially the idea that world religions provide solutions to the problem of meaning. More specifically, religions are salvific solutions to the troubling question of how human suffering can be reconciled with the justice of God/divinity. The unique Twelver Shi‘i salvific solution to this problem of meaning is the combination of three main elements: 1) imamate as the constant divine guidance after the death of Prophet Muhammad; 2) occultation of the Twelfth Imam; and 3) a universal redemptive theology of martyrdom based on the tragic death of Prophet’s grandson, Husayn in 680 CE. All of these elements were lacking in mainstream Sunni Islam……. Read more

Iran to restore its UNESCO-inscribed churches

In line with the goal of jumpstarting the tourism industry, Iran has allotted some $370,000 to the restoration of the UNESCO-inscribed churches that are located in northwest of the country.

“A sum of 14 billion rials (roughly $370,000) will be channeled into restoration plans for the UNESCO-inscribed churches in Iran,” Cultural Heritage, Tourism and Handicrafts Organization Deputy Director Mohammad-Hassan Talebian told IRNA on Sunday.

“The identity of historical churches [in the country] must be preserved and the cultural heritage organization makes efforts to promote them by the means of organizing religious ceremonies and conducting conservation projects,” Talebian added.

The official made the remarks during a visit to Qareh Klise (the Monastery of Saint Thaddeus), an ancient Armenian monastery that played host to a religious gathering by the Christians in a mountainous landscape of West Azarbaijan province, adjacent to the borders of Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Turkey.

The organization also plans to document a total of 450 Armenian churches and 150 Assyrian ones, ILNA quoted Talebian as saying on Saturday.

Qareh Klise has always been a place of high spiritual value for Christians and other inhabitants in the region. Every summer, it hosts gatherings of pilgrims coming from Iran and Armenia to observe special religious ceremonies such as Holy Communion and baptism.

Together with St. Stepanos Monastery and the Chapel of Dzordzor, St. Thaddeus was placed on the UNESCO World Heritage list in 2008 under the title “Armenian Monastic Ensembles of Iran”.

UNESCO says these edifices are examples of outstanding universal value of the Armenian architectural and decorative traditions.

Source: www.tehrantimes.com

CIA Confirms Role in 1953 Iran Coup

National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 435

Posted – August 19, 2013

Edited by Malcolm Byrne

See for more information: nsarchive.gwu.edu/NSAEBB/NSAEBB435

Iran’s New Islamic Penal Code

Authors: Professor Intisar Rabb and Marzieh Tofighi Darian Read more

The Qur’an: Text, Society And Culture’ Conference

‘The Qur’an: Text, Society And Culture’ Conference

Thursday 10 – Saturday 12 November 2016

SOAS, University of London

Convenors: Prof. M.A.S. Abdel Haleem and Dr Helen Blatherwick

Thursday 10 November

(Khalili Lecture Theatre, SOAS main building)

9.00–9.45 Coffee and Registration

9.45–10.00 Opening Address (Professor M.A.S. Abdel Haleem)

10.00–11.30 Panel 1: Rhyme, Style, and Structure (chair: M.A.S. Abdel Haleem)

Devin J. Stewart (Emory University), ‘Rhyme and Rhythm as Criteria for Determining Qur’anic Verse Endings in the Work of Ibn Sa‘id al-Dani and the “Counters”’

Marianna Klar (SOAS, University of London), ‘The Structuring Force of Rhyme in The Long Qur’anic Suras’

فايز حسان سليمان أبو عمرة (جامعة الأقصى)، السياق القرآني ودوره في فهم النصوص القرآنية

11.30–12.00 Coffee Break

12.00–1.00 Panel 2: Textual History and Chronology (chair: tbc)

Anne-Sylvie Boisliveau (Sorbonne University), ‘Diachronic Composition of the Qur’anic Text: When Argumentative Analysis Helps Chronology’

Adam Flowers (University of Chicago), ‘Reconsidering Genre in Qur’anic Studies’

1.00–2.30 Lunch

2.30–4.00 Panel 3: Language, Ideas, and Discourse (chair: Deen Mohamed)

Nathaniel A. Miller (University of Cambridge), ‘Quranic Isra’ and Pre-Islamic Hijazi Imagery of Rule’

عبد الرحيم بن أحمد شنين (جامعة قاصدي مرباح ورقلة)، درء شبهة تغليب المذكّر على المؤنث عند العرب من خلال القرآن الكريم

Thomas Hoffmann (University of Copenhagen), ‘Taste My Punishment and My Warnings (Q. 54:39): On the Torments of Tantalus and Other Painful Metaphors of Taste in the Qur’an’

Friday 11 November

(Brunei Gallery Lecture Theatre, Brunei Gallery)

9.30–11.00 Panel 4: Narration and Narrative (chair: Marianna Klar)

Jessica Mutter (University of Chicago), ‘Dramatic Form and Nested Dialogue: The Use of iltifat in the Qur’an’

Hamza M. Zafer (University of Washington), ‘The Patriarchs in the Qur’an’

Shawkat M. Toorawa (Yale University), ‘Daughters in the Qur’an’

11.00–11.30 Coffee Break

11.30–1.00 Panel 5: Law (chair: Abdul Hakim al-Matroudi)

Joseph Lowry (University of Pennsylvania), ‘Legal Language and Theology in the Qur’an: Excuse, Repentance, Forgiveness, and Fulfillment’

A. David K. Owen (Harvard University), ‘Certainty in Interpretation: Causal Knowledge in Ibn Hazm’s Account of Zahiri Qur’anic Exegesis in al-Ihkam fi usul al-ahkam’

Ramon Harvey (Ebrahim College), ‘Interpreting Indenture (mukataba) in the Qur’an: Q. 24:33 Revisited’

1.00–2.45 Lunch

2.45–4.45 Panel 6: Contemporary Approaches (chair: Devin Stewart)

Ulrika Mårtensson (Norwegian University of Science and Technology), ‘‘Abd al-Aziz Duri: The Significance of his Historiographical Model for Current Qur’an Research’

عبد القادر بوشيبة (جامعة تلمسان)، لسانيات النص وآفاق قراءة النص القرآني

نزار خورشيد مامه (جامعة دهوك)، نظرية التلقي في القرآن الكريم: دراسة تحليلية

Joseph Lumbard (American University in Sharjah), ‘Decolonialising Qur’anic Studies’

Saturday 12 November

(Brunei Gallery Lecture Theatre, Brunei Gallery)

9.30–11.00 Panel 7: Theology and Tafsir (chair: tbc)

Hannah Erlwein (SOAS, University of London), ‘A Reappraisal of Classical Islamic Arguments for God’s Existence: Fakhr al-Din al-Razi’s Tafsir as a Case in Point’

مشرف بن أحمد الزهراني (جامعة الأمير سطام بن عبد العزيز)، القيم المعنوية والجمالية في استطرادات القاسمي التفسيرية

Aisha Geissinger (Carleton University), ‘al-Maturidi’s Exegetical Use of Variant Readings: The Strange Case of “harf Hafsa”’

11.00–11.30 Coffee Break

11.30–12.30 Panel 8: Political Dimensions of Interpretation and Translation 1 (chair: Hannah Erlwein)

Teresa Bernheimer (SOAS, University of London), ‘Opposition Groups, Coins, and the Qur’an’

Walid Saleh (University of Toronto), ‘The Political in tafsir: Q. 43:44 as an Example’

12:30–1.45 Lunch

1.45–3.15 Panel 9: Political Dimensions of Interpretation and Translation 2 (chair: Helen Blatherwick)

Noureddine Miladi (Qatar University), ‘The Representation of the Qur’an in the Western Media’

Burçin K. Mustafa (SOAS, University of London), ‘The Translation of Ambiguous Qur’anic Terms in the Realm of Doctrine Propagation’

Johanna Pink (University of Freiburg), ‘Contested Form, Contested Meaning: Literal, Literary and Exegetical Translations of the Qur’an in Contemporary Indonesia’

3.15–3:30 Closing Remarks (Professor M.A.S. Abdel Haleem)

Further Information:

If you would like further information on the conference series, please visit the conference website at https://www.soas.ac.uk/quran-2016/. This will be updated on an ongoing basis.

For general enquiries, please contact the conference administrator at quran.conference@soas.ac.uk. For academic enquiries only contact Helen Blatherwick at hb20@soas.ac.uk.

Mystical Poems of Rumi

Translated from the Persian by A. J. Arberry

Annotated and prepared by Hasan Javadi

Foreword to the new and corrected edition by Franklin D. Lewis

General Editor, Ehsan Yarshater

The University of Chicago Press – Chicago & London

PDF – Link

http://www.wordscascade.com/index_htm_files/rumi.pdf

The translations in this volume were originally published in two books.

The first volume, including the first 200 poems, or ghazals, appeared in 1968 under the title ** Mystical Poems of Rūmī 1, First Selection, Poems 1– 200 **. It was part of a UNESCO Collection of Representative Works and was accepted in the translation series of Persian works jointly sponsored by the Royal Institute of Translation of Teheran and United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO)….. Read more

The claim that Islam lacks an Enlightenment is an age-old cliche

In this interview with Anna Alvi and Alia Hübsch, Prof. Angelika Neuwirth says that the claim that Islam lacks an Enlightenment is an age old cliché, and that it is pride in the Enlightenment that continues to lead people to believe that Western Culture is superior to Islam

Prof. Neuwirth, your book Der Koran als Text der Spätantike (The Koran as a late antique text) runs to over 800 pages. In it, you try to find a European door to the Muslims’ holy book. What exactly do you mean by the “European” perspective on the Koran?

Angelika Neuwirth: The book itself explains what I mean. I try to show that when one reads the Koran historically, one encounters the very same traditions that Europeans consider fundamental to their culture. The Koran is read as a proclamation, in other words as a message to people who were not yet Muslims at the time. After all, they only became Muslims through the proclamation. This perspective shows that back then, the same problems were being discussed on the Arabian Peninsula and in the surrounding late antique world, which was in a way later perceived as being the foundation of Europe. In other words, we all come from a common genesis scenario, something that was only obscured by subsequent historical developments.

So it is less about finding a “European” door to the Koran and more about common late antique elements or the influence of antiquity, or about the so-called “Orient” and “Occident” being able to claim these elements as exclusively their own …

Neuwirth: But the fact of the matter is that they do. Both in the Orient – in other words in Islam’s conventional self-perception – the assumption is that right from its very origins, Islam was essentially different from the culture around it and that with it, something completely new came into the world. Prior to this was the Age of Jahiliyyah, i.e. the Age of Ignorance, an era held in low esteem that does not really deserve much recognition.

In the West too, Islam is seen as completely different, i.e. something that doesn’t belong to Western culture. These are ancient codes regarding what constitutes “difference”. They do not apply to this day, but came about because of earlier shifts in power or balances of power.

Would you then reject the notion that Islam still needs an Enlightenment or that reason and science are at odds with faith?

Neuwirth: The claim that Islam lacks an Enlightenment is an age-old cliché. Pride in the Enlightenment – even though this pride has died down somewhat – continues to lead people to believe that Western Culture is way ahead of Islam.

There has never been a comprehensive secularisation movement in Islamic history for the simple reason that the sacred and the secular already existed side by side in Islam. Moreover, the imbalance of power between East and West has not always been as it is today. For a very long time, the Islamic culture of knowledge was far superior to that in the West or outside the Islamic world as a whole. This was not least the result of the fact that the Islamic culture was more advanced in terms of media.

For example, paper was being manufactured in the Islamic world since as far back as the eighth century. This in turn made it possible to disseminate huge amounts of texts, which was definitely not the case in the West at that time. Without a doubt, more than 100 times more Arabic texts were brought into circulation during this period than was the case in the West. Right up until the fifteenth century, people in the West relied on parchment, which was very expensive and hard to come by.

What image of women and humans does the Koran portray?

Neuwirth: Of course, the Koran is not a reference work for social behaviour. Many people assume that all of Islam’s norms can be found in the Koran. But that is not the intention behind the Koran. The Koran was a proclamation to people who were familiar with other norms and were willing to call these norms into question. The Koran highlights discussions about various norms. The fact that the relatively small number of legally relevant instructions were then put together in a system and made part of the Islamic canon of norms, the Sharia, is a different matter altogether.

The subsequent literature on law does not reflect the same situations as the Koran. This is particularly evident in the case of the image of women in the Koran, which is completely different to the image of women in Islamic law literature. Here in particular, the Koran takes a revolutionary step forward: it puts woman on the same level as man before God. That is truly unique for this period. Both genders will be judged in the same way at the Last Judgement. This may seem irrelevant today, but it isn’t. At that time, gender equality between men and women was completely unthinkable. There were even discussions as to whether women had souls at all. Women were judged very ambivalently, and their legal status in many pre-Islamic societies was incredibly unfavourable. The Koran also puts women on a par with men on important secular matters too; they have rights and are even entitled to inherit. In other words, women are not legally incapacitated.

In “God is beautiful”, Navid Kermani speaks of the aesthetic dimension of the Koran. What is this aesthetic dimension?

Neuwirth: If one reads and interprets the Koran as a kind of information medium – as many contemporary Koranic researchers do – one does not do justice to it. The Koran is heavily poetic and contains a whole range of messages that it imparts at a semantic level – not at all explicitly, not at all unambiguously; it gets these messages across through poetic structures; if it didn’t, it wouldn’t be as vivid as it is. What makes the Koran unique is its complexity, its multiple layers, the fact that it speaks at different levels. On the one hand, of course, that is the huge aesthetic attraction. However, it is also, if you like, hugely attractive in rhetorical terms or in terms of its power of conviction.

While it might be possible to sum up the mere information in the Koran in a short newspaper article, the effect would not have been the same. It really is about enchantment through language. Language itself is also praised in the Koran as the highest gift that humankind received from God. Naturally, this is related to knowledge. Language is the medium of knowledge. This is why one should never on top of everything else accuse the Islamic culture of being averse to knowledge. The entire Koran is basically a paean to knowledge, the knowledge that is articulated through speech.

What parallels are there between the Koran and the religious scriptures of the Jews and the Christians? What exactly is it that makes the Koran stand out or what new aspect did the Koran bring?

Neuwirth: The Koran must have brought something new; after all, it came into the world so many hundreds of years after the last and previous holy scripture – about 500 years after the New Testament. On the one hand, I would say that it is its insistence that knowledge is an immensely important part of human life and of human religious life too. This is not, for example, important in the New Testament. The New Testament focuses on other things; as does the Torah, the Old Testament, in other words the Hebrew Bible.

The focus on knowledge is undoubtedly something new that was not there before. This is linked to its genesis in Late Antiquity, a time when people were simply willing to give priority to knowledge. What’s more, another novelty is that the universalisation of the message, a message that is now sent to all people, plays a major role in the Koran.

or is there much understanding in the Koran for the Jewish view that the Jews are God’s chosen people. The Koranic voice rejects an election such as this; instead, humans as a whole take the place of the chosen few. It also rejects the election of the Christians, who put themselves in the place of the Jews. There are no chosen ones; there is just humankind as a whole, humans who follow certain models, but who cannot appeal to any privileges as the chosen people; neither in the way the Jews invoke Abraham or the Christians Christ. Such invocations do not help when one is standing before God; instead, everyone is responsible for himself or herself and has to account for his or her actions.

In other words, everyone can build up his or her own personal relationship to God without the need for any kind of intermediary in between?

Neuwirth: Yes, you could put it like that, although the Koran itself is, to a certain extent, a kind of intermediary, a medium that makes it easier to reach this state. By fulfilling one’s ritual obligations – above all by praying – and reciting the Koran, a door is opened to the believer that is not open to others. This is, however, a ritual verbal door, but not a privilege that is granted to one person or is based on a procedure or a figure of salvation.

Interview conducted by Anna Alvi and Alia Hübsch

© Qantara.de 2013

Prof. Dr. Angelika Neuwirth read Arabic Studies, Semitic Studies and Classical Philology at the Freie Universität Berlin and in Tehran, Göttingen, Jerusalem and Munich. Following her habilitation, she worked as a guest professor at the University of Jordan in Amman from 1977 to 1983. She was director of the Orientinstitut der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft (Oriental Institute at the German Oriental Society) in Beirut and Istanbul from 1994 to 1999. She is currently working as a professor at the Freie Universität in Berlin. The main focus of her research is on the Koran and Koranic exegesis, modern Arab literature in the Levant, Palestinian poetry and the literature of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. In June 2013, she was awarded the Sigmund Freud Prize for academic prose for her Koranic research.

Translated from the German by Aingeal Flanagan

Editor: Lewis Gropp/Qantara.de

Source: Qantara.de

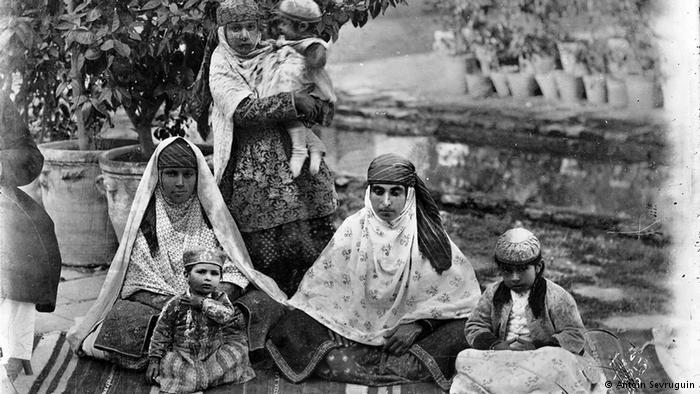

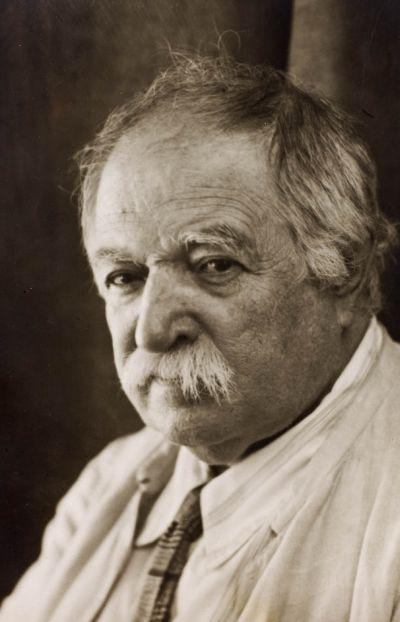

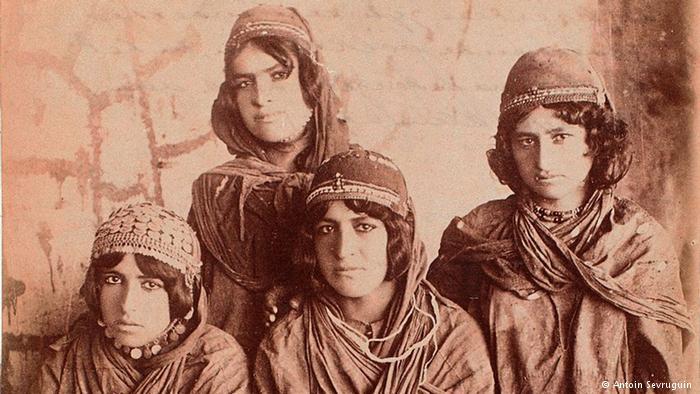

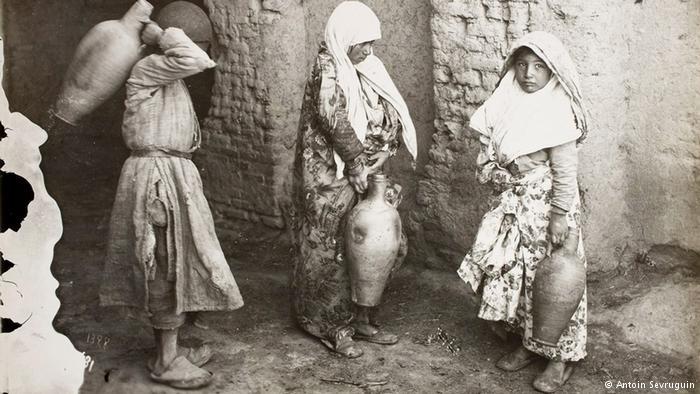

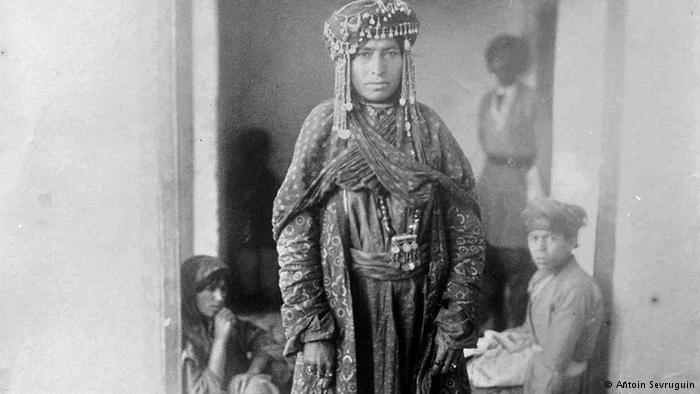

The women of Iran – 120 years ago

Antoin Sevruguin, the father of Iranian society photography, captured portraits of Iranian women in the early 20th century, from well-known ladies at the court to women from various tribes around the country.

A photo of women in the Qajari era, taken by Antoin Sevruguin, Iran’s leading photographer at the turn of the twentieth century

The Armenian-Iranian photographer Sevruguin, born in mid-19th century Tehran during the Qajari era, studied painting and photography in Tbilisi, Georgia and was appointed as the official Qajari court photographer under Naser ad-Din Shah

One of Sevruguin′s favourite subjects was portraits of the common people. This picture shows two Iranian tribal women sitting at a “korsi” (heated table)

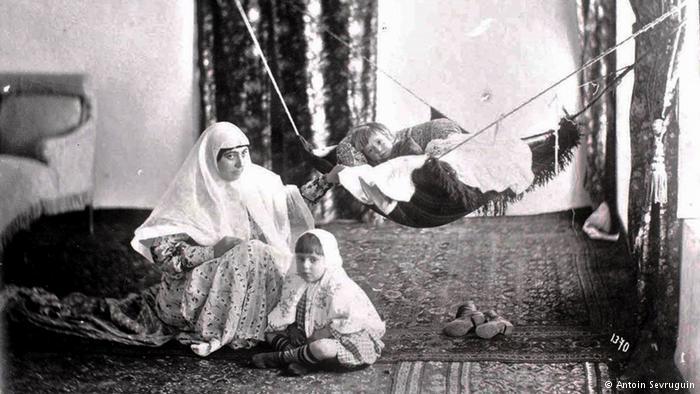

Sevruguin shot this photo of an Iranian mother with her children more than 100 years ago. With the aid of Persian army officers, he travelled around the country documenting the diversity of the Persian people

This portrait of a rural woman feeding her baby is one of his masterpieces

Two girls from the Shahsevan tribe, from the region that is now the Republic of Azerbaijan. “Shahsevan” means adherents of the Shah

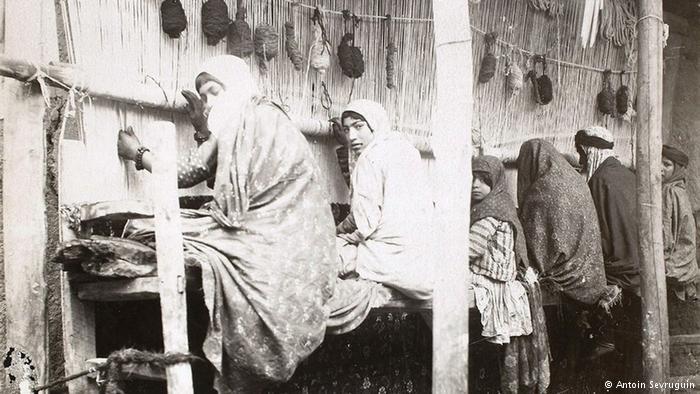

Many tribal girls and women in the Qajari era were employed in carpet production. The three Qajari rulers Fath Ali Shah, Naser ad-Din Shah and Mozaffar ad-Din Shah made a particular effort to revive this old tradition

The society photographer Sevruguin was also interested in the underclass of his time. This photo depicts five beggar women

Kurdish girls in the Qajari era: Sevruguin′s journeys through Iran also took him to the country′s northwestern territory, which is inhabited by Kurds to this day

These three Qajari-era women embody the ideal of feminine beauty at the time, showing off monobrows and moustaches. Women who weren′t blessed with these beauty features helped nature along with make-up

Three girls with water jugs. Shia Islam, already becoming increasingly independent from the state during the 19th century, spread across almost all parts of Qajari society. The girls′ head coverings, for example, signalise the public′s religiosity

Kurdish dancers and musicians during Iran′s Qajari era. The Armenian-Iranian photographer Sevruguin not only travelled domestically but also made several trips to Europe to keep up to date on photography equipment and technique

A traditional head covering as shown in this picture is one of the most important characteristics of Iranian female tribal dress. Sevruguin shot portraits of large parts of the Iranian population, but the majority of his work was destroyed in 1908 as Iran proceeded to a constitutional monarchy

Source: qantara.de